-

Proposal for a visual media exhibition

with the participation of students of the Master of Film at the Dutch Film Academy, Amsterdam -

Get my films

Buy DVDs online at www.momento-films.com -

IZKOR

slaves of memory

Documentary film | 1990 | 97 min | color | 16mm | 4:3 | OV Hebrew ST -

Common Archive Palestine 1948

web based cross-reference archive and production platform

www.commonarchives.net/1948 - Project in progress - -

Montage Interdit [forbidden editing]

With professors Ella (Habiba) Shohat and Robert Stam / Berlin Documentary Forum 2 / Haus der Kulturen der Welt / June 2012 -

Route 181

fragments of a journay in Palestine-Israel

Documentary film co-directed with Michel Khleifi | 2003 | 272 min [4.5H] | color | video | 16:9 | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST

-

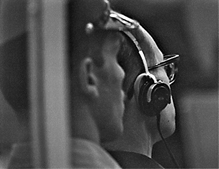

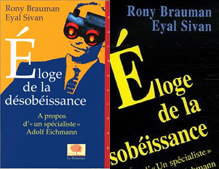

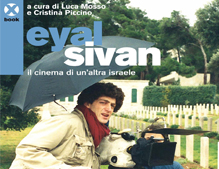

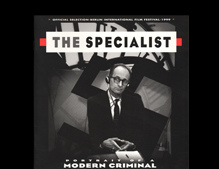

The Specialist

portrait of a modern criminal

Documentary film | 1999 | co-author Rony Brauman | 128 min | B/W | 4:3 | 35 mm | OV German, Hebrew ST -

Jaffa

the orange's clockwork

Documentary film | 2009 | 88 min | color & B/W | 16:9 | Digital video | OV Arabic, Hebrew, English, French ST

-

Montage Interdit

www.montageinterdit.net

Web-based documentary practice. A production tool, archive and distribution device | project in progress

-

Common State

potential conversation [1]

Documentary film | 2012 | 123 min | color | video | 16:9 split screen | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST -

Towards a common archive

testimonies by Zionist veterans of 1948 war in Palestine

Visual Media exhibition | Zochrot Gallery (Zochrot visual media lab) | Tel-Aviv | October 2012 - January 2013

-

I Love You All

Aus Liebe Zum Volk

Documentary film co-directed with Audrey Maurion | 2004 | 89 minutes | b/w & color | 35mm | OV German, French ST

The Specialist dir. Eyal Sivan Opens Thurs. Nov 16 at the Little Theatre.

THE 1961 TRIAL of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann has already had its apotheosis as transformed art ; Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem : A Report on the Banality of Evil remains one of the great books... well, ever. Eyal Sivan’s film, The Specialist, which accords the credit of "inspired by" to Arendt’s remarkable document, can’t hope to surpass her achievement. Instead, it highlights the theatrical elements of the trial, offering a self-conscious counterpoint to Arendt’s portrait of utterly non-self-reflexive evil.

Culled from more than 500 hours of video footage shot by American documentarian Leo T. Hurwitz, Israel’s decision to prosecute Eichmann the way it did amounted essentially to a show trial, and it was accordingly decided to document the proceedings as thoroughly as possible), The Specialist helpfully collapses the eight-month trial into a two-hour film. There are some intrusive digitalized effects, and I think the aggressive, guitar-feedback-soaked score is an ahistorical misstep, but first and foremost the film succeeds because it has no greater goal than introducing you to Adolf Eichmann, mass murderer.

Ostensibly for his own protection, Eichmann spent the entire trial contained in a cube of bulletproof glass, ever watched over by two guards. Slender, balding, and sharp-nosed, constantly poring over the stacks of documents gathered about him, still snapping to attention whenever he’s called upon to speak, the man responsible for coordinating transports of Jews to the death camps sits with an indifferent smirk as his crimes are tallied. Petty even in his meticulousness (we see a diagram he draws up of Nazi hierarchy ; it could have been taken from some dreadfully boring book, with perfectly straight lines threading between its pedantically itemized boxes), Eichmann seems too much the stiff-necked fusspot to have many friends, yet it’s easy to imagine him tending to a garden or a small, yapping dog with exasperated devotion. As Arendt realized, and as this flawed but essential document confirms, it is precisely his mediocre nonentity that is so terrifying : Longing to stare down a monster, we find only a pathetic, pencil-pushing bureaucrat. Which is even worse.