-

Proposal for a visual media exhibition

with the participation of students of the Master of Film at the Dutch Film Academy, Amsterdam -

Get my films

Buy DVDs online at www.momento-films.com -

IZKOR

slaves of memory

Documentary film | 1990 | 97 min | color | 16mm | 4:3 | OV Hebrew ST -

Common Archive Palestine 1948

web based cross-reference archive and production platform

www.commonarchives.net/1948 - Project in progress - -

Montage Interdit [forbidden editing]

With professors Ella (Habiba) Shohat and Robert Stam / Berlin Documentary Forum 2 / Haus der Kulturen der Welt / June 2012 -

Route 181

fragments of a journay in Palestine-Israel

Documentary film co-directed with Michel Khleifi | 2003 | 272 min [4.5H] | color | video | 16:9 | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST

-

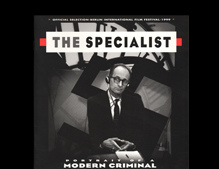

The Specialist

portrait of a modern criminal

Documentary film | 1999 | co-author Rony Brauman | 128 min | B/W | 4:3 | 35 mm | OV German, Hebrew ST -

Jaffa

the orange's clockwork

Documentary film | 2009 | 88 min | color & B/W | 16:9 | Digital video | OV Arabic, Hebrew, English, French ST

-

Montage Interdit

www.montageinterdit.net

Web-based documentary practice. A production tool, archive and distribution device | project in progress

-

Common State

potential conversation [1]

Documentary film | 2012 | 123 min | color | video | 16:9 split screen | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST -

Towards a common archive

testimonies by Zionist veterans of 1948 war in Palestine

Visual Media exhibition | Zochrot Gallery (Zochrot visual media lab) | Tel-Aviv | October 2012 - January 2013

-

I Love You All

Aus Liebe Zum Volk

Documentary film co-directed with Audrey Maurion | 2004 | 89 minutes | b/w & color | 35mm | OV German, French ST

In the midst of some melancholy ruminations in Edward Said: The Last Interview (2004), the late literary critic and political commentator remarks that the “useless” strategy of suicide bombing, embraced by some despairing Palestinians since the advent of the second intifada, mirrors the useless and ineffectual policies of the Israeli state. Said’s explication is much more lucid and straightforward than many of the speculations concerning suicide missions that have recently appeared in the popular press. Far too many commentators appeal to vulgar assumptions concerning Islamic conceptions of Jihad, or what the French political scientist Olivier Roy rightly terms “the cliché references to the seventy-two houris, or perpetual virgins, who are expecting the martyr.” Roy points out, in the midst of potted explanations of suicide attacks, many mainstream pundits invoke hoary notions of “Koranic Martyrdom” instead of nationalist and ethnic motivations. Yet Roy’s own attempt to explain these missions by appealing to a “Western tradition of individual and pessimistic revolt” seems equally myopic in its failure to address concrete political realities. His new clichés summing up “globalized Islam” have proved, perhaps unsurprisingly, appealing to conservative commentators eager to blame Western radicalism, instead of Islam, for the rash of suicide attacks—e.g. David Brooks’ charmingly named “Trading Cricket for Jihad” in the Aug. 4, 2005 edition of The New York Times. Of course, those who honestly attempt to explain the political genesis of acts that have horrendous consequences for innocent civilians become vulnerable to being labeled covert “apologists” for terror. (See, for example, the attacks on so-called “root causes” analyses of terrorism by the British academic Norman Geras in The Wall Street Journal and The Guardian.)

These admittedly extra-cinematic reflections are a prelude to tackling some of the critical quandaries raised by Hany Abu-Assad’s prize-winning film, Paradise Now, winner of the Best Director Award at this year’s Berlin film festival. Abu-Assad, a Palestinian filmmaker who has lived in the Netherlands since 1981, takes on the onerous task of fictionalizing the last hours of Said (Kais Nashef), a supposedly prototypical suicide bomber.

Unlike facile journalists, the well-meaning filmmaker attempts to locate Said’s personal and political anguish within a specific Palestinian milieu and set of concerns: there is a scrupulous effort to condemn suicide bombing while simultaneously engaging in an idiosyncratic analysis of Said’s personal descent into terrorism that would undoubtedly arouse the ire of Norman Geras if he deigned to attend a Palestinian film. Unfortunately, Abu-Assad and Bero Beyer’s ultra-schematic script provides Said with such a generous swath of backstory that political considerations are frequently subsumed by rather ham-fisted forays into pop psychology.

With opening sequences featuring a checkpoint inspection reminiscent of similar scenes in disparate films on the Israeli-Palestinian crisis and widescreen vistas of Nablus, a battle-scarred city on the West Bank (where much of the film was shot), Paradise Now’s implicit argument links the soured dreams of inhabitants of the Occupied Territories with the yearnings for political martyrdom which propel the narrative. We first glimpse Said and his friend Khaled (Ali Suliman) as they service a car owned by Suha, the Western-educated daughter of Abu Assam, a recently martyred Palestinian “freedom fighter,” in a ragtag chop shop. Although both Khaled and Said are soon recruited for a suicide mission, the appearance of the glamorous Suha (played by a Belgian-born actress, Lubna Azabal, who has appeared in films by Andre Téchiné and Tony Gatlif) injects the film with its didactic thrust by insisting that there is a difference between principled resistance and the lethal altruism which finds expression in suicide bombing. Although it’s difficult not to agree with Suha’s secular radicalism and opposition to self-defeating terrorist schemes, her strategically placed admonitions to Said become entirely subservient to her role as a spokesperson for Abu-Assad’s moral stance. When, for example, at a pivotal moment in the film, Said returns to Nablus after having second thoughts about his mission of doom, Suha counters his assertion that “as long as there’s occupation, there will be a need for sacrifice” with the suggestion that he may be inadvertently giving Israel an “alibi” for its repressive policies.

Paradise Now is a bit too calculating in aligning its gloss on internal Palestinian political debates with the contours of a political thriller. Like Mervyn Le Roy’s Two Seconds (1932), a film framed by Edward G. Robinson’s imminent death in the electric chair, Abu-Assad’s parable is tethered to the eventual death of its hapless protagonist. From the other end of the spectrum, a recent Israeli film, Eytan Fox’s Walk on Water (2004), mirrors Paradise Now’s implicit stance that eventual rapport between Israelis and Palestinians depends upon the hope of personal transformation. Fox’s film chronicles a hard-hearted Mossad agent’s change of heart from unrepentant anti-terrorist hit man to incipient peacenik. Abu-Assad’s conversation piece, while less willfully upbeat, similarly blurs psychological trauma and brute political realities. Rather glibly, Abu-Assad posits that Said’s decision to become a suicide bomber originates in shame over his father’s collaboration with the Israelis. Perhaps it is stating the obvious to maintain that commercial films often reduce complex political phenomena to moral or psychological bromides. Nevertheless, as John Collins points out while reviewing the recent book Growing Up Palestinian: Israeli Occupation and the Intifada Generation in the Journal of Palestine Studies, “seemingly irrational violence is animated bya ‘simple pragmatism’ rooted in confinement, hopelessness, and a perceived lack of effective tactical alternatives. The second intifada thus appears as an index of all the (largely negative) developments of the 1990s: continued structural violence, a deteriorating relationship between young people and their leaders, the growth of gangsterism and corruption, and the creeping bantustanization of Palestine.” A few more intimations of this sort of “structural violence” and a bit less amateur psychoanalysis would have prevented audiences from viewing Said’s plight as an anomalous case study.

Curiously enough, the strongest moments of Paradise Now are perversely comic. In a key scene that chronicles the shooting of Khaled and Said’s “martyr videos,” technical snafus force Khaled to repeat his carefully scripted spiel several times as the men’s recruiter, Jamal (Amer Hlehel), munches on a pita. This type of black humour drives home the nature of what the Situationist Gianfranco Sanguinetti once termed the “spectacle of terrorism.” Sanguinetti, however, referred to maneuvers orchestrated by the Italian state intended to discredit the ultra-left. As Abu-Assad’s protagonists mouth heroic platitudes by rote, it is clear they’ve become embroiled in a self-inflicted spectacle spurred on by ineradicable pessimism.

If features such as Paradise Now and Abu-Assad’s 2002 film Rana’s Wedding (a rather self-consciously arty tale of a woman who must surmount the twin obstacles of Israeli checkpoints and family opposition to marry the man she loves) are only intermittently successful in conveying the sources of Palestinian pain, a proliferation of recent documentaries—often highlighting recurrent motifs such as checkpoints, refugee camps, and the looming presence of the Israeli “security barrier” being constructed alongside the Occupied Territories—have proved considerably more edifying. Of all these documentaries, Eyal Sivan’s and Michel Khleifi’s Route 181: Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel (2004) is by far the most courageous and aesthetically satisfying. A film with almost no chance of being commercially distributed in North America, Route 181 has had a troubled history. In what a press release calls an “unprecedented move,” a screening scheduled for March 2004 at Le Festival du Cinéma du Réel was abruptly cancelled. The festival’s co-sponsors disseminated a statement defending their action by asserting that the film posed “a risk to public order” and arguing that, despite being the product of a collaboration between an Israeli filmmaker and his Palestinian cohort, it might even encourage “anti-Semitic and anti-Jewish statements and acts in France.” In the US, where one might assume that debate on these matters is even more fevered, the film was merely victimized by boneheaded reviews. The Film Society of Lincoln Center, in a curious act of negative publicity, published a sneering review by Harlan Jacobson in Film Comment at the same time it sponsored two screenings of the film at its annual Film Comment Selects series. Jacobson complained that the filmmakers’ attempt to ferret out the often abrasive opinions of Israelis and Palestinians was little more than a wearing effort to elicit the views of the “vox populi” in lieu of the usual voices of political elites; an equally dismissive reviewer from New York’s The Jewish Week merely compared the participants’ rants to the cacophony of “talk radio.”

Although Route 181 is certainly a riposte to mainstream Israeli opinion, it actually reflects a vital, if frequently overlooked dissident strain within Israel that is more likely to receive more (however grudging) attention in Ha’aretz than The New York Times. For both Israelis and Palestinians who believe that certain suppressed elements of Zionist history should be brought to light, this epic documentary represents a triumph of conscience over expediency and is about as far from an incitement to anti-Semitism as one could imagine. As leisurely—and as subtle—a polemic as Robert Kramer’s similarly episodic Route One/USA (1989), Sivan and Khleifi’s documentary is actually a carefully structured road movie that, during a four-and-a-half hour running time, retains a kernel of utopian optimism despite the pessimism evinced by many of the interviewees.

The filmmakers’ decision to re-trace the route of the 1947 UN Partition plan, quickly abandoned after the 1948 war, captures the grim origins of the ongoing crisis with mordant irony. This trek—from the south of Israel near Gaza to the north near the Lebanese border—evokes an ambiguous historical past. On the one hand, the Partition might be rightly pilloried as an attempt on the part of the imperial powers to carve up Palestine and shortchange the indigenous population; on the other, the thoroughgoing abandonment of the dream of a bi-national state that was once embraced by secular Jews such as Hannah Arendt, Noam Chomsky, and I.F. Stone represents a lost opportunity for peaceful co-existence. (The current, all-too-chimerical status of this concept is driven home in Paradise Now, when, in the midst of filming his martyr video, Khaled refers to the once-vaunted egalitarian notion of bi-nationalism as a “sell-out.”) Alternately, but even more importantly, the emphasis on post-1948 travails highlights the chasm between Israel’s enshrinement of a “war of independence” and liberation and the Palestinian elegy for a period of dispossession and devastation commonly known as the Nakba (“catastrophe”). In some respects, Route 181’s unabashed focus on a host of former Arab villages now transformed into Israeli communities is enough to arouse the ire of diehard Zionists. But a reiteration of historical data that has even been acknowledged by Benny Morris, a staunchly Zionist historian often mislabeled a “post-Zionist,” would not be enough to make this film’s stance distinctive. Sivan and Khleifi explore how many Israelis appear to both affirm and disavow this legacy of dispossession, and the relationship of this apparent political schizophrenia to the ongoing historical impasse within Israel/Palestine.

In fact, one of the film’s most revelatory sequences pithily interweaves past historical woes and the contemporary snare of self-inflicted historical amnesia. At the museum of Kibbutz Yad Mordechai, an elderly, Polish-born Israeli tour guide (and former “pioneer”) maintains that, unlike recent Jewish settlers, “we didn’t colonize.” There is, however, an odd slippage between his assertion that Arabs merely “fled” to Gaza during 1948 and his de facto admission that Arabs were expelled. He goes on, moreover, to bemoan the increasing birth rate of the Arab population and expresses his fear that Israel’s Jewish character might eventually be endangered. These platitudes are followed by a shot of a statue that greets visitors at another kibbutz, which the filmmakers describe on their web site as a “Stalinist-looking monument”—a reminder that the ideology of the earliest Zionist settlers encompassed both an Old Left emphasis on class consciousness and a racist view of their Arab neighbors that differed little from the views of right-wingers such as Sharon.

Most of the Sephardim — Jews from Arab countries referred to as Mizrahim in Hebrew — who emigrated, or were forcibly repatriated, to Israel after 1948 were less than entranced by the discourse of Labour Zionism elucidated by the Polish tour guide. Unlike much of the historical literature and the majority of documentary films that address the Israeli-Palestinian crisis, Route 181 offers a nuanced view of the Sephardic community. As Ella Shohat argues in Sephardim in Israel: Zionism from the Standpoint of its Jewish Victims,

“Although Zionism claims to provide a homeland for all Jews, that homeland was not offered to all with the same largess. Sephardi Jews were first brought to Israel for specific European-Zionist reasons, and once there they were systematically discriminated against by a Zionism that deployed its energies and material resources differentially, to the consistent advantage of European Jews and to the consistent detriment of Oriental Jews.”

While even Peace Now, a group often assumed to be at the forefront of Israeli liberalism, has often stigmatized Sephardi Jews as reactionary and inflexibly anti-Arab, Sivan and Khleifi recognize that Arab Jews in Israel actually represent an important link to the historical past and a bridge to reconciliation between Israelis and Palestinians. For example, early in the film, a weary Palestinian man recalls that “Jews lived among Arabs in Arab countries for many years…[The] problem isn’t between Jews and Arabs, but between occupiers and occupied.” This lament is soon followed by an interview with an Iraqi Jewish grocer, whose positive memories of his childhood in Iraq and fondness for Arabic is accompanied by a pronounced cynicism towards his government.

Towards the end of Sivan and Khleifi’s pilgrimage, a Moroccan woman recounts her youthful recruitment in the late 50s as a “broom” by the Israeli government—an agent instructed to lure fellow Jews to Israel. She concludes that she was “hoodwinked” by the Israelis; as Shohat explains,

“From the early days of Zionism, Sephardim were perceived as a source of cheap labor that had to be maneuvered into immigrating to Palestine.”

Finally, near the conclusion of the film, a Tunisian Jewish woman, still distraught over the death of her son in Lebanon, blurts out that “Sharon and Arafat should be shot with their mothers”—a sentiment that might be shared by both Jews and Palestinians who only feel disgust for the bureaucratic machinations of so-called “leaders.” If anything unites the well intentioned, but notably flawed, Paradise Now and the magisterial, if scandalously caricatured and neglected (at least in North America) Route 181, it is this spirit of skepticism towards received wisdom and entrenched authority. Whether the caveats of filmmakers, who might like to think of themselves as the unacknowledged legislators of the world but are often quite powerless, will be heeded is, of course, another matter.