-

Proposal for a visual media exhibition

with the participation of students of the Master of Film at the Dutch Film Academy, Amsterdam -

Get my films

Buy DVDs online at www.momento-films.com -

IZKOR

slaves of memory

Documentary film | 1990 | 97 min | color | 16mm | 4:3 | OV Hebrew ST -

Common Archive Palestine 1948

web based cross-reference archive and production platform

www.commonarchives.net/1948 - Project in progress - -

Montage Interdit [forbidden editing]

With professors Ella (Habiba) Shohat and Robert Stam / Berlin Documentary Forum 2 / Haus der Kulturen der Welt / June 2012 -

Route 181

fragments of a journay in Palestine-Israel

Documentary film co-directed with Michel Khleifi | 2003 | 272 min [4.5H] | color | video | 16:9 | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST

-

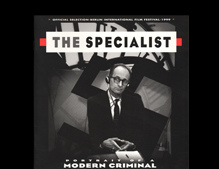

The Specialist

portrait of a modern criminal

Documentary film | 1999 | co-author Rony Brauman | 128 min | B/W | 4:3 | 35 mm | OV German, Hebrew ST -

Jaffa

the orange's clockwork

Documentary film | 2009 | 88 min | color & B/W | 16:9 | Digital video | OV Arabic, Hebrew, English, French ST

-

Montage Interdit

www.montageinterdit.net

Web-based documentary practice. A production tool, archive and distribution device | project in progress

-

Common State

potential conversation [1]

Documentary film | 2012 | 123 min | color | video | 16:9 split screen | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST -

Towards a common archive

testimonies by Zionist veterans of 1948 war in Palestine

Visual Media exhibition | Zochrot Gallery (Zochrot visual media lab) | Tel-Aviv | October 2012 - January 2013

-

I Love You All

Aus Liebe Zum Volk

Documentary film co-directed with Audrey Maurion | 2004 | 89 minutes | b/w & color | 35mm | OV German, French ST

The Specialist Un Specialiste (Documentary -- B&W -- French)

By Eddie Cockrell

"The Specialist," from Israeli-born, Paris-based Eyal Sivan, is a singularly assured, sure-to-be-controversial documentary that recasts footage from the 1961 Jerusalem trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann into a hypnotic dance of bureaucratic stubbornness, highlighting the very ordinariness of this eccentric, relentlessly unrepentant monster. Cutting-edge, unique item is a must for -- but not limited to -- Jewish and docu fests and has limited theatrical possibilities if handled properly. It's assured a long life in ancillary markets (including the classroom) on video and particularly videodisc, where depth and breadth of pic's technical wizardry and audacious narrative presentation can be debated by scholars of both the docu form and the Holocaust.

Organized into 13 sections punctuated by blackouts, the film immediately announces itself as something other than a straight presentation of the material: the prologue is composed of disembodied voices from the trial recordings and a discordant, foreboding score.

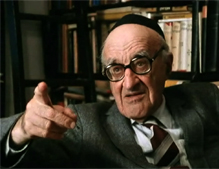

Looking like a constipated accountant, the man who specialized in the "Jewish issue" and was charged with the mass deportation of Jews to concentration camps from 1941-45 is first seen cleaning his glasses and gingerly cleaning the desk in his glass booth with a handkerchief.

As the trial progresses, Eichmann emerges as a master of denial and obfuscation, freely admitting the crimes were committed but insisting that he was "weak and powerless" to stop it. He invokes a parade of deflections -- "That was unfortunate, but it wasn't my fault," "I had orders to carry out" and endless other variations.

Defense lawyer Robert Servatius hardly says a word on behalf of his client, while the three Israeli judges of German origin each approach the accused in a different manner. The audience at the trial is glimpsed only briefly (a few protesters are escorted out), yet an entire section of the film is devoted to the testimony of survivors (whose faces are digitally superimposed on the booth's glass).

Sivan says the project came about when co-scripter Rony Brauman was given a copy of Hannah Arendt's "Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil" and was particularly taken with her assertion that Eichmann was an ordinary man whose "normality is much more terrifying than all atrocities together." The scriptwriters' approach is clearly reverent yet distinctly mischievous, managing to relish unintentional sight gags afforded by Eichmann's bizarre behavior while acknowledging the drab but hypnotic countenance of the man.

This dichotomy is shown in the film's two most prominent digital effects: In the first, the guards flanking Eichmann are subtly erased and replaced (few in the Berlin premiere audience seemed to notice), while the second, climactic effect suggests that the spirit of the evil civil servant is still alive in a cubicle somewhere, just waiting to be summoned.

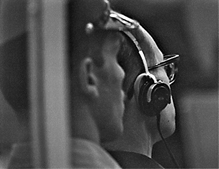

Tech aspects explore fresh ways of presenting primitively shot material. Israel pacted with ABC, which hired blacklisted docu filmmaker Leo T. Hurwitz to design and oversee a four-camera, two-inch video setup recording the trial (with angles selected by him in real time) from the chambers specially built in the main auditorium of Jerusalem's House of the People. (Hurwitz's own film on the subject, "Verdict for Tomorrow," won Emmy and Peabody awards in 1961.) Finished film is sculpted from the 350 surviving hours of the 500 shot over eight months, with the sound replaced by the higher-quality tapes recorded by the Voice of Israel radio.

The jarring score is of special note, with the unorthodox guitars, trombones and glass harmonica of the listed quartet supplemented by Tom Waits' "Russian Dance" over the closing credits.

High-profile docus both, James Moll's "The Last Days" and "The Specialist" were presented as special screenings in the Berlinale's official program, heading a pan-sectional theme of movies about the Holocaust, racism and discrimination dubbed "Documents Against Forgetting."