-

Proposal for a visual media exhibition

with the participation of students of the Master of Film at the Dutch Film Academy, Amsterdam -

Get my films

Buy DVDs online at www.momento-films.com -

IZKOR

slaves of memory

Documentary film | 1990 | 97 min | color | 16mm | 4:3 | OV Hebrew ST -

Common Archive Palestine 1948

web based cross-reference archive and production platform

www.commonarchives.net/1948 - Project in progress - -

Montage Interdit [forbidden editing]

With professors Ella (Habiba) Shohat and Robert Stam / Berlin Documentary Forum 2 / Haus der Kulturen der Welt / June 2012 -

Route 181

fragments of a journay in Palestine-Israel

Documentary film co-directed with Michel Khleifi | 2003 | 272 min [4.5H] | color | video | 16:9 | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST

-

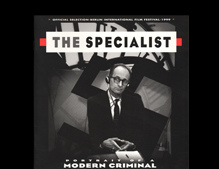

The Specialist

portrait of a modern criminal

Documentary film | 1999 | co-author Rony Brauman | 128 min | B/W | 4:3 | 35 mm | OV German, Hebrew ST -

Jaffa

the orange's clockwork

Documentary film | 2009 | 88 min | color & B/W | 16:9 | Digital video | OV Arabic, Hebrew, English, French ST

-

Montage Interdit

www.montageinterdit.net

Web-based documentary practice. A production tool, archive and distribution device | project in progress

-

Common State

potential conversation [1]

Documentary film | 2012 | 123 min | color | video | 16:9 split screen | OV Arabic, Hebrew ST -

Towards a common archive

testimonies by Zionist veterans of 1948 war in Palestine

Visual Media exhibition | Zochrot Gallery (Zochrot visual media lab) | Tel-Aviv | October 2012 - January 2013

-

I Love You All

Aus Liebe Zum Volk

Documentary film co-directed with Audrey Maurion | 2004 | 89 minutes | b/w & color | 35mm | OV German, French ST

Eyal Sivan was taking photos of a model exhibiting designer clothes. He had chosen as a background what he thought was a deserted refugee camp outside Jericho. With sun, sand, empty homes, a camera and a model, Sivan started clicking away. Then he noticed movement. Children, who seemed to have come from the center of the earth, suddenly surrounded them. Surprised by their presence, Sivan began to search for the source of this human movement. He followed the children around to discover that the seemingly deserted site still had life in it.

Most of the 65,000 Palestinian refugees who had filled the camp between 1947 and 1967 were gone. They went as refugees for the second time to Jordan; and later, maybe, to south Lebanon; and… and… and… Nevertheless some 3,000 refugees still live there. They have been joined by Bedouins, who come to the camp as part of their travels.

Twenty-two-year-old Sivan, an Israeli who has been in trouble with the Israeli government for his leftist views, decided he must return, to try and tell the story of these refugees almost forgotten by the world.

A few years later Sivan was in France studying film production. The Georges Pompidou Center announced a film festival for anthropological films. First prize was 25,000 French Francs (US$4125). Sivan, with help from Thibaut de Corday, established a film production company called Dune Vision. He found a bank willing to extend them credit, put together a film crew, and came back to Aqabat Jaber refugee camp in November 1986. He then spent two weeks on location, shooting what was called Aqabat Jaber - Passing Trough. The film was edited in time for the festival and won first prize.

The Film

The 86-minute documentary successfully conveys the mood of the refugees in this particular camp. The dullness of life in the camp, the endless waiting, the emptiness, are conveyed in every frame of the film.

The 38 years these Palestinian refugees have been waiting to return to their homes is not only the focus but also the context of the entire film. By living with the refugees, the director and crew were able to break through the self-consciousness most people who have lost everything and are left only with the memories of their homes and of the orange groves, which once provided their livelihood.

The film has no particular story, with a beginning, middle, and end. It is also not journalistic reportage relating in numbers and figures the what, when, why, and how. It is simply a collection of pictures, a montage perhaps, of various everyday scenes in these camps. You feel that these scenes have happened for years, and you have every reason to believe they will continue to happen for some time to come. And although every one of the 28 people who speak in the film (all speak in Arabic - there is no narration or introduction to the film) tell of their own individual background, their common story is the same. It is a story of nostalgia for a place that once belonged to them; one they fiercely claim a right to return to.

Politics

The Palestinian refugees’ strong desire to return to their homes is not given political emphasis. Why these Palestinians became refugees, who is responsible for the perpetuation of their situation and why they are not allowed to return is never discussed in the film. It is unclear whether the director planned it this way, whether he wants to deal with the problem of refugees on a universal level. No Israeli soldiers appear in the film - although they are posted a couple hundred meters from the camp - nor does the Palestinian-Israeli conflict come up in any of the conversations. The only direct evidence of the Israeli occupation is the sound of an Israeli jet flying over the camp during one of the interviews.

Sivan says that to have introduced a political element would have made his film the same as any other film about the “conflict” and the number of people who would see it would be limited to those already converted. The head of the PLO office in London agreed with this analysis. Faisal Aweidah told the director that having won first prize in a respected film festival means the film will be seen, and this is a plus.

Not everyone who saw the film, however, agreed. The PLO’s UNESCO representative, Omar Masalha, sharply criticized the film’s lack of a political angle. The head of the PLO Paris office, Ibrahim Sous, a respected pianist, simply had no time to see the film.

Sivan visited the Jerusalem area last month and showed a video of the film to a few friends and journalists. He plans to return in the fall to take the film to Aqabat Jaber and show it to the camp residents. But meanwhile, Sivan is running around the world looking for buyers, in order to pay back his nearly US$100,000 bank loan.